Working With Emotions, Healing Our World

Today is Veterans Day, 2025. I want to acknowledge all those who have served,  suffered, and even lost their lives so that the rest of us may live relatively free and open lives. Veterans include not only those who served in the military, but also the families of those who died in service. However, there are many who have sacrificed for the cause of freedom and liberation within our own shores. The first black children integrated into schools, the first students who spoke out against an unjust Vietnam War, and those who currently challenge human participation in climate change, racial violence and societal hatred. With great respect for those who have served our military, I also want to recognize all who have suffered and been wounded in life, yet continue to face the world with courage.

suffered, and even lost their lives so that the rest of us may live relatively free and open lives. Veterans include not only those who served in the military, but also the families of those who died in service. However, there are many who have sacrificed for the cause of freedom and liberation within our own shores. The first black children integrated into schools, the first students who spoke out against an unjust Vietnam War, and those who currently challenge human participation in climate change, racial violence and societal hatred. With great respect for those who have served our military, I also want to recognize all who have suffered and been wounded in life, yet continue to face the world with courage.

Many of us feel shaken, frightened, and insecure these days—whether we put on a strong front or collapse wrapped in the fabric of time and space on our bed. We are human, and being human is a complex endeavor. Humans hurt, and humans heal. Hurt humans hurt humans. But healing humans, heal humans.

I work as a coach, chaplain, and teacher. And I am often on call for people in my life who need me. I don’t deserve any medals for this, because, in truth, it is very healing for me. I’ve been fortunate to structure my life around spiritual work, both individually and within communities. It allows me to take the pain I’ve endured and transform it into empathy and understanding for others. Though my pain is by no means comparable to the suffering many have faced, it has a very real effect on me. My wounds hold me back as I try and protect them behind defensive walls of blame, resentment and inebriation.

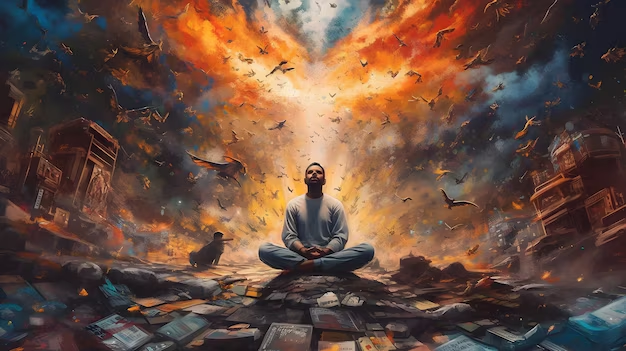

I started my journey with meditation when I was most confused about how to move forward. Each step forward seemed to be met with a step back—sometimes a frozen moment, sometimes a lashing out, sometimes a dive into extreme tequila to numb the pain of indecision. These may sound like champagne problems—or in my case, a tequila-and-cocaine problem—but it still kept me from fully participating in life. I was always healing, always beginning again, but the object of healing was undefined, so this process only supporting my impairment. It wasn’t until I began looking at the things that were blocking me that I could begin to heal.

I started my journey with meditation when I was most confused about how to move forward. Each step forward seemed to be met with a step back—sometimes a frozen moment, sometimes a lashing out, sometimes a dive into extreme tequila to numb the pain of indecision. These may sound like champagne problems—or in my case, a tequila-and-cocaine problem—but it still kept me from fully participating in life. I was always healing, always beginning again, but the object of healing was undefined, so this process only supporting my impairment. It wasn’t until I began looking at the things that were blocking me that I could begin to heal.

The Buddhist path, the 12-step systems, and many therapeutic and spiritual paths encourage us to start with acknowledging the problem. For the alcoholic, that acknowledgment is simply their addiction and their powerlessness over it. Buddhists, acknowledging the pain we endure and look at how trying to deny, avoid or struggle with that truth creates great suffering. This acknowledgment doesn’t have to be measured against anyone else’s experience—it’s our own pain we’re recognizing. Just as some alcoholics enter recovery with what their friends might see as a minimal problem, and others are urged to enter treatment because their addiction is overt, once we step onto the path of recovery, our journeys are equal. The same is true for the Buddhist path. Once we acknowledge our own pain, we don’t have to compare it to anyone else. However, we can see commonality as we begin to see the pain in the world. Reflexively, once we see the pain in the world, we can begin to understand it more deeply within ourselves.

In healing communities, and discussion groups we are often encouraged to speak from the “I” posture. When we present grand ideas about how the world should be, we evoke resistance and counter propositions. But no one can argue when we express our true feelings about our own pain and suffering. Being honest with ourselves in the present moment, acknowledging how we are hurting, is the first step toward transformation. And by transformation, I don’t mean we will somehow escape our pain for a “better” life. Alcoholics will always be alcoholics, whether sober or not. Buddhists will always face human pain, whether enlightened or not. In fact, it’s possible that the Buddha experienced more pain after his enlightenment than he did before. Trungpa, Rinpoche said that spiritual transformation is not turning lead into gold. It is turning lead into lead. However it is lead we’ve acknowledged and understood so that we can to learn to work with it.

The Buddha’s journey began when he realized there was a world beyond the walls of his father’s palace. As a young prince, he was given every luxury and every training to succeed his father as head of the Shakya clan. Yet, there was an itch inside him—a sense of unease that even all his wealth and privilege could not soothe. Like many of us, especially in our youth, that discomfort manifested as an urge to see the world outside the palace walls. He eventually rebelled, snuck out, and was shocked by the pain and suffering he saw in the world. This sparked his desire to understand the nature of pain. The more he exposed himself to suffering, the more deeply he felt it, and it became clear that his path was not to escape pain, but to understand it—both his own suffering and that of others—in hopes of alleviating the suffering we create.

Ultimately, the Buddha realized that none of us can escape pain. But as is said, while pain is inevitable, suffering is optional. We amplify our suffering by refusing to acknowledge our pain. Once we do, we can begin to process it and transform it into a tool for understanding others. Understanding others, whether we agree with them or not, is a profound purpose in life. By de-emphasizing the importance of our self-cherishing, we can look beyond the walls we build around ourselves and start to see how we can communicate, connect, and ultimately heal the world around us.