Right Action in the Face of Hatred

I woke up today feeling crushed. It’s odd to wake up in the sweaty arms of defeat. Then I sat for morning meditation and a personal check-in. Feelings are part of our reality—but they are not reality. They are expressions of a part of our being that is constantly changing. However, when we become triggered, our feelings solidify into narrative environments that we interpret as reality.

We freeze, believe, identify. Then we’re off to the races as we script our story with ourselves as the protagonist, whether it be victim or hero. The more we are triggered, the more our universe feels real. But what’s real is that we are at the center of that universe. This very solid Me rolled from bed into a universe of defeat.

We freeze, believe, identify. Then we’re off to the races as we script our story with ourselves as the protagonist, whether it be victim or hero. The more we are triggered, the more our universe feels real. But what’s real is that we are at the center of that universe. This very solid Me rolled from bed into a universe of defeat.

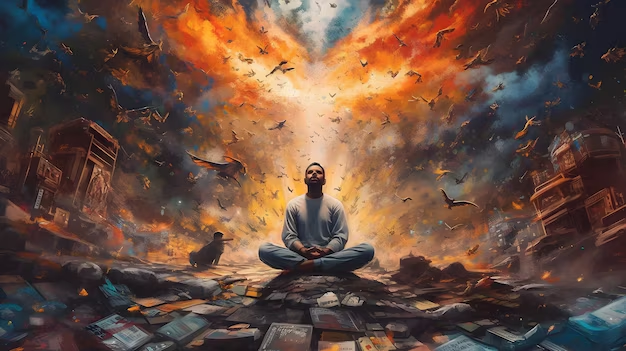

However, once I sat for my morning meditation and adjusted my posture, my brain changed. A posture of gentle confidence changes the perspective. Seat your ass, and your mind will follow. As my mind relaxed its grip, I could see how exaggerated feelings like fear and doubt had been obscuring gratitude, clarity and strength. I did a “check-in and simply noted what I saw and felt—without interpretation. Just so. This is what there is. Sadness, fear, anxiety. But also, calmness, clarity and gratitude.

And none of my feelings accurately predict the future.

We live in violent times, and often feel beaten down even when we’re not directly affected. Fear inflames our feelings and makes them personal. This is not new. In my childhood, progressive leaders were murdered in the streets. Four unarmed students were shot for protesting a war in which their country poured napalm on villages. The 1970s brought recession; only three decades before, a full depression. African Americans have long faced violence from neighbors, police, and their own Armed Forces. Native populations have had their cultures starved into silence. An affluent Black district in Tulsa was looted and burned—and wasn’t widely reported for decades.

Violence and ignorance have always been a part of our country’s history. It’s just more meaningful when it’s happening to us. In real time. The immediacy intensifies its impact on our nervous system. We catastrophize, lose perspective, and imagine futures we cannot know. We see only what panic shows us and miss the fullness of our actual experience. We forget that it has always been this way and for some, its has been much much worse. Take this personally is profound egotism. It’s not about only ourselves. It’s about our world, and our ability to remain strong in the face of the storm.

But, we are part of our world, and so Compassion begins with us. Not exaggerating our self importance and our pain, but activating our empathy. If we settle our heart, mind, and body, we can see past the fog of panic. By simply taking our seat and sitting tall, we access natural wisdom. That’s wisdom, not wisdoom. Not believing the worst, but seeing what there is – everything there is. Like sediment settling in water, clarity dawns. We see what is—not an exaggeration of fear.

But, we are part of our world, and so Compassion begins with us. Not exaggerating our self importance and our pain, but activating our empathy. If we settle our heart, mind, and body, we can see past the fog of panic. By simply taking our seat and sitting tall, we access natural wisdom. That’s wisdom, not wisdoom. Not believing the worst, but seeing what there is – everything there is. Like sediment settling in water, clarity dawns. We see what is—not an exaggeration of fear.

Wisdom is seeing without judgment or expectation. This kind of seeing, beyond self-interest, is foundational to what the Buddha called right action. It’s tempting to go numb or reactive. To armor ourselves in ideology or turn away. But there’s another response. A deeper, braver one:

Compassion.

When we freeze or fight, we can pause, take our seat, and choose to respond. Compassion isn’t weakness. It isn’t blind forgiveness or passive acceptance. It’s not about being nice.

Compassion is a revolution.

Not one that screams or fights fire with fire, but a revolution of presence. A rebellion against dehumanization. A refusal to become what we oppose. It asks us to see the humanity in those who suffer—and sometimes even in those who cause suffering—without condoning harm or retreating into neutrality.

This kind of compassion isn’t sentimental. It’s a discipline. A practice. A path.

True compassion doesn’t dull our edge—it sharpens it. It helps us respond with precision and clarity. With compassion, our actions become more effective. Without it, we risk replicating the patterns we seek to dismantle. We fight fire with fire until everything is ash. With compassion, we fight fire with awareness, fierce love, and sanity.

The world doesn’t need more opinions. It needs grounded hearts. Hearts that can grieve. That can see suffering behind violence. That can stand up without being poisoned by hatred. That won’t be swayed by stupidity or false logic.

Compassion is bravery.

It’s brave to keep the heart open when it would be easier to shut it down. Brave to meet anger with understanding—not because we’re doormats, but because we’re warriors of spirit. It’s brave to weep when the world breaks, and still choose to return to our cushion, our vow to remain undaunted.

We can’t fix a world that has always been broken. But we can stay present and do what we can. Freaking out helps no one. But sitting in silence helps only ourselves. If a monk gains enlightenment in a cave and no one hears it…? It’s said the Buddha was reluctant to teach after awakening. But continual supplications, and empathy for those suffering moved him to act.

Acting from a seat of wisdom for the benefit of others is compassion.

When we feel broken-hearted, it’s not a weakness. It’s a doorway to power. If you’re angry—good. Let that fire be lit by clarity, not hatred. Let it be tempered by practice. Let it protect and uplift, not divide and destroy.

Combining stillness of our being, the Clarity of our Heart and the courage of our heart. That is warriorship. That is strength.

In this violent time, compassion is not a retreat.

It is a revolution.

A radical act of presence.

A refusal to collapse into cynicism.

So breathe.

Feel your heart.

Let yourself care.

Let that care guide your words, your actions, your presence.

The world is aching for it.

Sit your ass, and your mind will follow.

Free your heart—and the world will follow.

The ideal meditative state—clarity and acceptance—rests on the openness and settledness of the body, heart, and mind. However, life rarely offers us perfect conditions. For me, morning practice often begins with a scattered or resistant mind. The first step, then, is acceptance—meeting the mind as it is and not as I wish it to be.

The ideal meditative state—clarity and acceptance—rests on the openness and settledness of the body, heart, and mind. However, life rarely offers us perfect conditions. For me, morning practice often begins with a scattered or resistant mind. The first step, then, is acceptance—meeting the mind as it is and not as I wish it to be. Once again, meditation isn’t about fixing; it’s about seeing. The mind of meditation arises in awareness like a point in space. And as the space of awareness is relieved of the pressure to fix itself or chose a side, it remains loving and supportive. It is a state of grace. By stepping into the grace of awareness, we don’t need to force change—we simply allow what we notice to be with us, remembering none of it is as real, solid or urgent as our fear suggests. Trungpa Rinpoche famously wrote, “good, bad, happy, sad – all thoughts vanish like an imprint of a bird in the sky.” Once we release ourselves from the grip of control, we see everything as ephemeral, diaphanous and in dynamic transition. Sakyong Mipham calls this the displaysive activity of mind. All of our worries are the mind revealing itself. Many of our worries are kid fears. And like kids, they need to be loved and accepted, but not always believed.

Once again, meditation isn’t about fixing; it’s about seeing. The mind of meditation arises in awareness like a point in space. And as the space of awareness is relieved of the pressure to fix itself or chose a side, it remains loving and supportive. It is a state of grace. By stepping into the grace of awareness, we don’t need to force change—we simply allow what we notice to be with us, remembering none of it is as real, solid or urgent as our fear suggests. Trungpa Rinpoche famously wrote, “good, bad, happy, sad – all thoughts vanish like an imprint of a bird in the sky.” Once we release ourselves from the grip of control, we see everything as ephemeral, diaphanous and in dynamic transition. Sakyong Mipham calls this the displaysive activity of mind. All of our worries are the mind revealing itself. Many of our worries are kid fears. And like kids, they need to be loved and accepted, but not always believed.

In a world filled with endless information and impulses, the idea of simplifying life to a single breath may seem overly reductive, especially in contrast to the overwhelming chaos of our triggered states. And while chaos is part of life these days, perhaps there is a way to navigate this chaos. Instead of trying to control the flood of thoughts and data, we can shift our focus from the mind into action. And we can take that action one step at a time. The question becomes: What is the next right step?

In a world filled with endless information and impulses, the idea of simplifying life to a single breath may seem overly reductive, especially in contrast to the overwhelming chaos of our triggered states. And while chaos is part of life these days, perhaps there is a way to navigate this chaos. Instead of trying to control the flood of thoughts and data, we can shift our focus from the mind into action. And we can take that action one step at a time. The question becomes: What is the next right step? While it is important to be in the moment, each moment is leading to the next. To make this next authentic action practical, it helps to determine where we are going. If we have a commitment to work for the benefit of all beings then it becomes clear. By “all,” beings we are including ourselves. Helping others at the cost of our own wellness is not truly helpful. So, what is the next step that leads toward helpful engagement with our world? Once we know this, the next step we take is a natural action. By natural we mean not rooted in confusion or external expectation, but what needs to be done for the benefit of everyone, including ourselves. Taking that step will clarify the next step and in so doing reveal the journey ahead. We move toward helpfulness and harmony, and away from reactive patterns that keep us entangled in life’s struggles.

While it is important to be in the moment, each moment is leading to the next. To make this next authentic action practical, it helps to determine where we are going. If we have a commitment to work for the benefit of all beings then it becomes clear. By “all,” beings we are including ourselves. Helping others at the cost of our own wellness is not truly helpful. So, what is the next step that leads toward helpful engagement with our world? Once we know this, the next step we take is a natural action. By natural we mean not rooted in confusion or external expectation, but what needs to be done for the benefit of everyone, including ourselves. Taking that step will clarify the next step and in so doing reveal the journey ahead. We move toward helpfulness and harmony, and away from reactive patterns that keep us entangled in life’s struggles.

False binaries dominate our consciousness, good versus evil, left versus right, wonderful versus horrible. We live squeezed between these exaggerations. The Buddha taught that the truth lies not in extremes but in the “middle way.” This teaching urges us to be present in our lives and act rightly in the moment. Similarly, the 12-step traditions speak of “doing the next right thing.” According to the Buddha, the next right step depends on the specific circumstances of the moment. Instead of fabricating extremes, the middle way turns our attention to what’s really happening.

False binaries dominate our consciousness, good versus evil, left versus right, wonderful versus horrible. We live squeezed between these exaggerations. The Buddha taught that the truth lies not in extremes but in the “middle way.” This teaching urges us to be present in our lives and act rightly in the moment. Similarly, the 12-step traditions speak of “doing the next right thing.” According to the Buddha, the next right step depends on the specific circumstances of the moment. Instead of fabricating extremes, the middle way turns our attention to what’s really happening.

suffered, and even lost their lives so that the rest of us may live relatively free and open lives. Veterans include not only those who served in the military, but also the families of those who died in service. However, there are many who have sacrificed for the cause of freedom and liberation within our own shores. The first black children integrated into schools, the first students who spoke out against an unjust Vietnam War, and those who currently challenge human participation in climate change, racial violence and societal hatred. With great respect for those who have served our military, I also want to recognize all who have suffered and been wounded in life, yet continue to face the world with courage.

suffered, and even lost their lives so that the rest of us may live relatively free and open lives. Veterans include not only those who served in the military, but also the families of those who died in service. However, there are many who have sacrificed for the cause of freedom and liberation within our own shores. The first black children integrated into schools, the first students who spoke out against an unjust Vietnam War, and those who currently challenge human participation in climate change, racial violence and societal hatred. With great respect for those who have served our military, I also want to recognize all who have suffered and been wounded in life, yet continue to face the world with courage. I started my journey with meditation when I was most confused about how to move forward. Each step forward seemed to be met with a step back—sometimes a frozen moment, sometimes a lashing out, sometimes a dive into extreme tequila to numb the pain of indecision. These may sound like champagne problems—or in my case, a tequila-and-cocaine problem—but it still kept me from fully participating in life. I was always healing, always beginning again, but the object of healing was undefined, so this process only supporting my impairment. It wasn’t until I began looking at the things that were blocking me that I could begin to heal.

I started my journey with meditation when I was most confused about how to move forward. Each step forward seemed to be met with a step back—sometimes a frozen moment, sometimes a lashing out, sometimes a dive into extreme tequila to numb the pain of indecision. These may sound like champagne problems—or in my case, a tequila-and-cocaine problem—but it still kept me from fully participating in life. I was always healing, always beginning again, but the object of healing was undefined, so this process only supporting my impairment. It wasn’t until I began looking at the things that were blocking me that I could begin to heal.

Facing the possibility of change with an open heart, a strong back and a clear mind is nonviolent warriorship which is the seat of the bodhisattva. Connecting to our inner life force, we find a strength that can lead us forward. Sit down, rise up and meet the change. There is great strength in this. Finding false strength in what everybody else is doing or in reacting to what everyone else is doing, which is the same, are just expressions of being controlled by fear. On the other hand, bravery is sitting in the maelstrom, open and aware, feeling our fear and remaining open and clear. Doing this as a training practice every morning is how we remain spiritually fit and connected to our life.

Facing the possibility of change with an open heart, a strong back and a clear mind is nonviolent warriorship which is the seat of the bodhisattva. Connecting to our inner life force, we find a strength that can lead us forward. Sit down, rise up and meet the change. There is great strength in this. Finding false strength in what everybody else is doing or in reacting to what everyone else is doing, which is the same, are just expressions of being controlled by fear. On the other hand, bravery is sitting in the maelstrom, open and aware, feeling our fear and remaining open and clear. Doing this as a training practice every morning is how we remain spiritually fit and connected to our life. Peace is natural to the mind. As a natural state, the cessation of suffering is readily accessible. However, peace is not a fixed state. There is always suffering in our lives, and accepting our suffering is key to finding the peace that is already present. You might say peace is both intermittent and permanent. It is always there, but sometimes it becomes obscured by the tightness and difficulty that suffering induces.

Peace is natural to the mind. As a natural state, the cessation of suffering is readily accessible. However, peace is not a fixed state. There is always suffering in our lives, and accepting our suffering is key to finding the peace that is already present. You might say peace is both intermittent and permanent. It is always there, but sometimes it becomes obscured by the tightness and difficulty that suffering induces. Finally, the cessation of suffering is both the fruition of the path and a foundational state necessary for any creative endeavor. It is also an ongoing possibility. If we cling to the idea of cessation, we miss the point, turning something intermittent into something perceived as solid—another source of suffering. The possibility of peace is here now, even as we lose it by thinking about it. Peace is a felt sense. It is connecting to a part of our being that has always been there, and according to Buddhist thought, that peace is not diminished or changed by suffering.

Finally, the cessation of suffering is both the fruition of the path and a foundational state necessary for any creative endeavor. It is also an ongoing possibility. If we cling to the idea of cessation, we miss the point, turning something intermittent into something perceived as solid—another source of suffering. The possibility of peace is here now, even as we lose it by thinking about it. Peace is a felt sense. It is connecting to a part of our being that has always been there, and according to Buddhist thought, that peace is not diminished or changed by suffering.